Search

Mobile ID

Mobile phones and other devices can also provide portable digital identity credentials capable of authenticating users for a variety of online and offline transactions. The prevalence of mobile phones and the relatively low cost of some mobile IDs compared to a card-based system can make this an attractive option. In many countries, however, it would be difficult to deploy a mobile ID solution as the only identity credential, given that not everyone has a phone and network coverage may not be universal. Indeed, mobile-based systems are often deployed as optional or additional credentials to increase user convenience and choice.

|

Box 36. Moldova's Mobile eID In 2011, the Government of Moldova embarked on a governance modernization program to transform delivery of public services using information and communications technologies (ICT). One core priority of this initiative was to offer e-service providers a simplified way to integrate strong authentication and signature functionality into their services. In order to accomplish this, the government adopted a Mobile eID (MeID) solution along with a suite of shared platforms, including MPass (for strong authentication and single sign-on functionality across government information systems and e-services) and MSign (used to electronically sign documents and records and validate electronic signatures). MeID was launched in 2012 via a PPP that is described in Box 25. The MeID solution built on the existing PKI infrastructure and a strong foundational ID system, including the State Register of Population (SRP), which covers virtually the entire population and assigns each citizen a 13-digit personal identification number at birth. The SRP is the core source for identification information and underpins numerous other registers and systems. In addition, the government issues physical ID cards (which as of 2014, includes the option of a smart “eID” card that also offers digital authentication and signature capability). The MeID solution uses a SIM-based or client-side model to allow for mobile authentication and document signing. In order to enroll in this service, users first obtain a PKI-enabled SIM card through a mobile provider, who validates their identity against the SRP and generates a public and private key pair on the SIM. This SIM card then uses PKI encryption (i.e., digital signatures) to authenticate users via the MPass platform and secure e-signatures via the MSign platform. This solution provides a high level of assurance and legal force to electronic transactions, which can be used for a range of services including electronic tax filing, submitting electronic reports, and requesting e-services, etc.

|

In general, there are five main options for a implementing a mobile ID:

-

Smartphone apps. Smartphone-based apps can hold a virtual version of existing identity credentials, allowing people to avoid carrying a separate ID card—e.g., similar to the “cards” a person adds to their Google or Apple Wallet. These credentials allow users to quickly access and share identity data, (e.g., via a QR code), and may also offer the ability to authenticate this identity via a PIN, OTP, or FIDO-certified authenticator. Both India and Brazil have recently deployed ID apps of this kind.

-

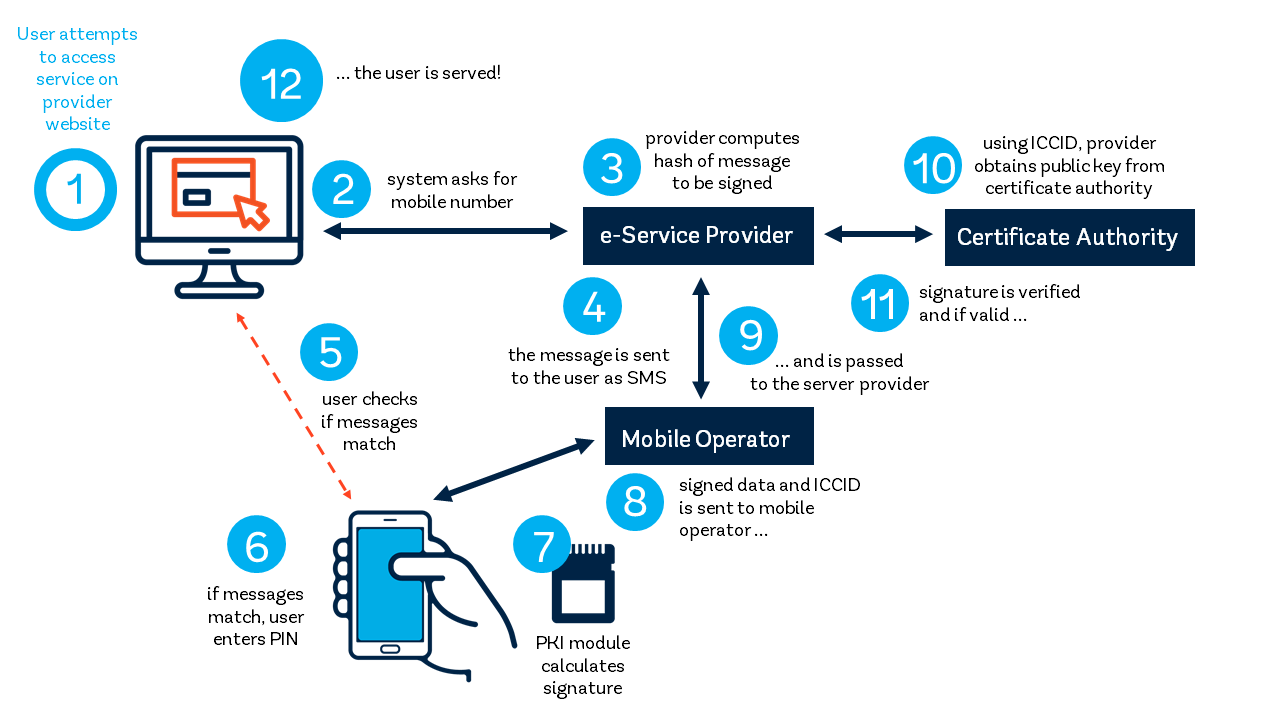

SIM-based PKI. Similar to smartcards, this model uses a PKI-enabled SIM card that allows the owner to authenticate themselves on the mobile device by using (1) secure elements on a crypto-enabled SIM card to manage the private key, (2) the handset for the entry of an additional factor (e.g., a PIN) to authenticate the user, and (3) the mobile operator’s network to send the result to the relying party. This model is used in countries such as Sweden, Finland, Estonia, and Moldova (see Box 36). This method requires a PKI-enabled SIM card similar to the chips embedded in smartcards, but can work using any type of mobile phone, including feature phones and smartphones.

-

Server-side PKI. In this model, authentication is done via a remote hardware security module (HSM) rather than on the mobile device itself, which means that a mobile phone with any SIM card can be used as long as it can sent and receive SMS. When a user activates the service, a transaction authentication number (TAN) is generated remotely by the authentication authority and sent to the phone via SMS, along with a hash value of the authentication message. The user then compares the TAN and hash value, and—if they are the same—enters their PIN, and the server signs the message with the PIN and HSM. This is the model used in Austria (see Box 37).

-

FIDO-enabled devices. In addition to running apps, FIDO-certified smart phones, laptops and tablets (which include all devices running Android 7 or higher and all Windows 10 devices) can provide secure multi-factor authentication (MFA) natively. FIDO MFA is enabled via a combination of an on-device biometric match or other “user gesture” such as a PIN to authenticate a person to their device, followed by a second factor—using public key encryption to authenticate against a server—that authenticates the device to the online service. This means that MFA can be delivered not only in a smartphone app, but also for transactions delivered via a browser; support for FIDO is embedded across all elements of the Android and Windows platforms. FIDO’s use of public key cryptography leverages a “lightweight” form of PKI.

-

Mobile network operator service. A mobile network operator can provide an authentication service for its customers, based on their registered information and/or transactions. This could use a variety of different technologies and could or could not be linked with a country’s foundational ID system. For example, the GSMA—a global association of mobile network operators—have developed a Mobile Connect, which is a federated digital identity solution that uses APIs based on OpenID specifications to allow people to log in or authenticate themselves when accessing websites.

|

Box 37. The Austrian virtual Citizen Card The Central Register of Residents (CRR) is a national information system that contains data about every resident of Austria (citizen and non-citizens). Austria mandates that all residents register their presence in the country, and the CRR contains the records of all these registrations. Each data record in the CRR has a 12-digit unique identifier, the resident’s full name, sex, date of birth, citizenship, and full address. Records of foreigners also contain passport data. While registration is mandatory, there is no equivalent requirement that every resident obtain a physical ID card. Instead, Austria has a virtual Citizen Card (CC) which can be installed on different devices, with smart cards and mobile phones being the two most prevalent interfaces used. In order for a resident to use a smartcard-based CC, they need the activated CC, a card reader, a PC connected to the internet and special software (Citizen Card Environment- CCE) at the user end, and, a special software “MOA-ID” at the service provider end that helps with authentication. Source: Slamanig, B. Z. 2013. On Privacy-Preserving Ways to Porting the. FIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, (pp. pp 300-314), cited in Privacy by Design: Current Practices in Estonia, India, and Austria. |